Retinal Vein Occlusion: Risk Factors and What Injections Can Do

Dec, 1 2025

Dec, 1 2025

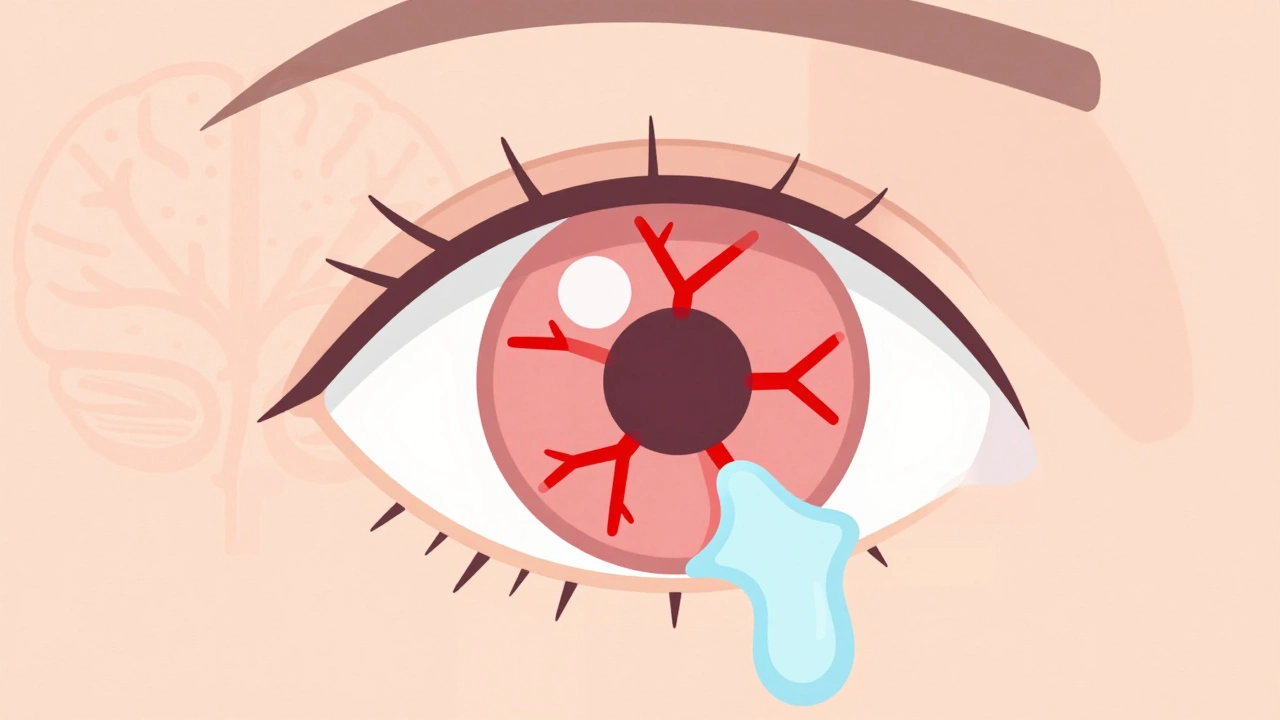

What Is Retinal Vein Occlusion?

Retinal vein occlusion (RVO) happens when a vein in the retina gets blocked, stopping blood from flowing out properly. The retina is the light-sensitive layer at the back of your eye that turns images into signals your brain understands. When blood backs up because of a blockage, fluid leaks into the retina, causing swelling-especially in the macula, the part responsible for sharp central vision. This leads to sudden, painless blurring or loss of vision in one eye.

There are two main types: central retinal vein occlusion (CRVO), which blocks the main vein, and branch retinal vein occlusion (BRVO), which affects smaller branches. BRVO is more common and often happens where a hardened artery presses down on a vein, like a kink in a garden hose. CRVO tends to be more severe and carries a higher risk of lasting vision loss.

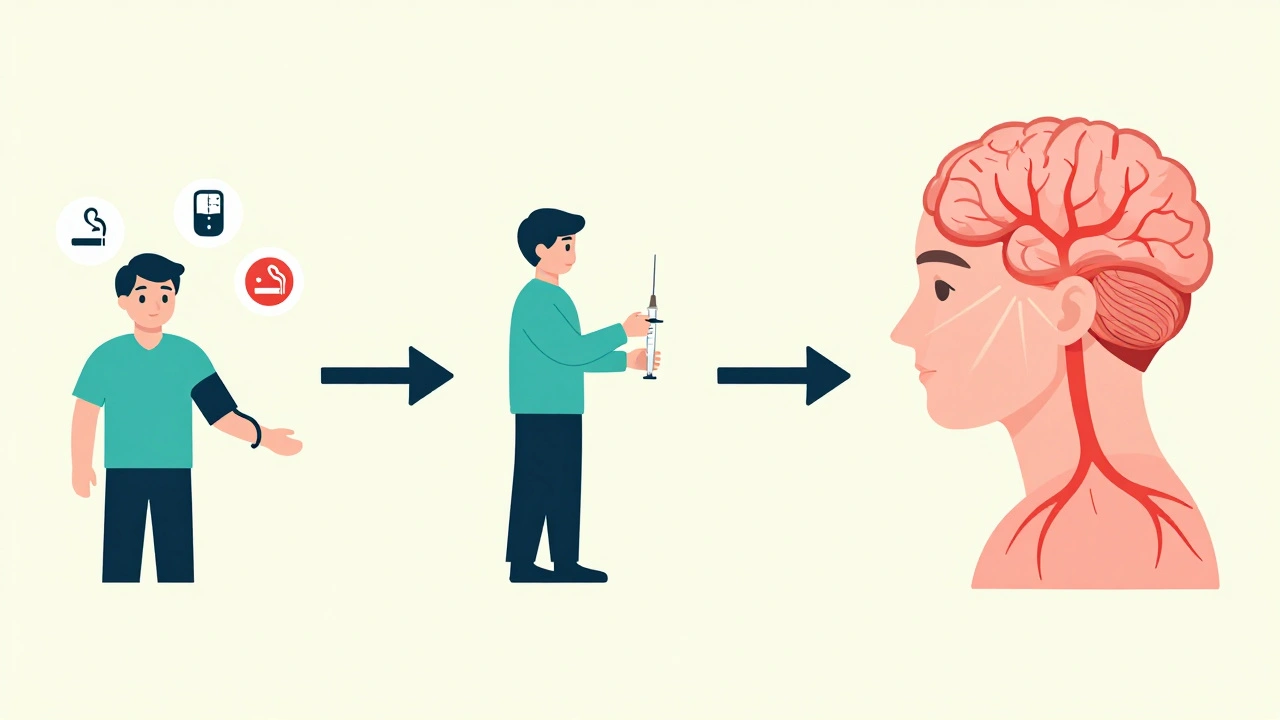

Who’s at Risk for Retinal Vein Occlusion?

Age is the biggest factor. Over 90% of CRVO cases happen in people over 55, and more than half of all RVO cases occur in those over 65. But it’s not just an older person’s disease-about 5 to 10% of cases happen in people under 45, especially women using birth control pills.

High blood pressure is the most common underlying issue. Up to 73% of CRVO patients over 50 have uncontrolled hypertension. Even if you don’t feel sick, long-term high blood pressure damages the tiny blood vessels in your eyes. Diabetes is another major player, affecting about 10% of RVO patients over 50. It weakens vessel walls and makes blood stickier, increasing the chance of clots.

High cholesterol also plays a role. If your total cholesterol is above 6.5 mmol/L, your risk goes up. About 35% of RVO patients have this level, regardless of age. Glaucoma, especially with high eye pressure, adds to the risk, particularly if the blockage occurs near the optic nerve.

Lifestyle factors matter too. Smoking is linked to 25-30% of cases. Being overweight or inactive contributes to poor circulation and hardened arteries. In younger patients, rare blood disorders like polycythemia vera, factor V Leiden, or protein S deficiency can trigger RVO. These conditions make blood more likely to clot.

How Do Injections Help?

Injections don’t fix the blocked vein. Instead, they treat the damage it causes-mainly macular edema, the swelling that blurs your vision. The two main types of injections are anti-VEGF drugs and corticosteroids.

Anti-VEGF drugs like ranibizumab (Lucentis), aflibercept (Eylea), and bevacizumab (Avastin) block a protein called vascular endothelial growth factor. This protein leaks fluid into the retina after a vein is blocked. By stopping it, these injections reduce swelling and often improve vision. Clinical trials show patients gain 15-18 letters on an eye chart after 6 months of monthly injections. That’s like going from 20/200 to 20/60 vision.

Corticosteroid injections, like the dexamethasone implant (Ozurdex), work differently. They reduce inflammation and swelling over a longer period. One implant can last up to 6 months. In the GENEVA study, nearly 28% of CRVO patients gained at least 15 letters of vision with Ozurdex, compared to 13% with a placebo.

Doctors usually start with anti-VEGF because it’s more effective for most people and has fewer long-term side effects. Steroids are saved for patients who don’t respond well, or who can’t handle frequent injections.

What’s the Treatment Process Like?

Before any injection, your eye doctor will do a full exam. That includes checking your vision, looking at the back of your eye, and doing an OCT scan. OCT uses light waves to create a detailed map of your retina’s thickness. If the central subfield thickness is over 300 micrometers, treatment usually starts.

The injection itself is quick-about 5 to 7 minutes. Your eye is numbed with drops, cleaned with antiseptic, and held open with a tiny clamp. The needle goes through the white part of your eye, just behind the iris. You might feel pressure, but not sharp pain. Afterward, you’ll see floaters or have a red spot on the white of your eye. That’s normal and fades in a few days.

Most people need monthly injections at first. Once swelling improves, the schedule changes to as-needed. Some clinics use a treat-and-extend approach: if your eye stays dry after 3 months, they stretch the next injection to every 2 months, then every 3. This reduces the number of visits by about 30% without losing results.

What Are the Risks of Injections?

Eye injections are generally safe, but they’re not risk-free. The most common side effect is a small red spot on the white of your eye-happens in 25-30% of cases. About 15-20% of people get a temporary spike in eye pressure, which usually goes down on its own. Floaters are common too, but they fade.

More serious problems are rare. Endophthalmitis, a serious eye infection, happens in only 0.02-0.1% of injections. That’s less than 1 in 1,000. Steroid implants carry extra risks: about 60-70% of people with natural lenses develop cataracts within a year, and 30% get high eye pressure that needs medication.

Some patients worry about the anxiety before each injection. Many say the fear is worse than the procedure. Clinics that do dozens of injections a day have streamlined the process, but the emotional toll is real. One patient on a support forum said she missed appointments because the stress became too much-even though her vision kept improving.

Cost and Access to Treatment

Anti-VEGF drugs are expensive. Ranibizumab and aflibercept cost around $2,000 per dose in the U.S. Bevacizumab, which is the same drug used for cancer but repackaged for the eye, costs about $50. Because of this, many safety-net clinics use bevacizumab for most RVO cases, while private practices tend to use the brand-name versions.

Insurance often covers the approved drugs, but copays can still be high. One patient reported paying $150 per injection, which added up quickly. The Ozurdex implant costs around $2,500 out-of-pocket, but it lasts longer, so fewer injections are needed.

By 2025, biosimilar versions of these drugs are expected to hit the market, which could cut costs significantly. There’s also a new delivery system called Susvimo, a tiny implant that slowly releases ranibizumab into the eye. It’s already approved for macular degeneration and is being tested for RVO. If it works, patients might only need injections every 3-6 months instead of monthly.

What’s Next for RVO Treatment?

The future of RVO treatment is moving away from one-size-fits-all. Doctors are now using OCT angiography to see exactly how blood flows in the retina. This helps predict who will respond best to anti-VEGF versus steroids.

Gene therapy is on the horizon. RGX-314, a one-time injection that makes your eye produce its own anti-VEGF protein, is in Phase II trials. If successful, it could mean one treatment instead of dozens.

Another promising approach combines aflibercept with OPT-302, a drug that blocks a different growth factor. Early results suggest this combo works better for stubborn swelling that doesn’t respond to standard therapy.

By 2024, the American Academy of Ophthalmology plans to update its guidelines to reflect this shift toward personalized treatment. The goal isn’t just to save vision-it’s to reduce the burden of monthly visits, lower costs, and improve quality of life.

Can You Prevent Retinal Vein Occlusion?

You can’t always stop it, but you can lower your risk. Control your blood pressure. Keep your cholesterol and blood sugar in check. Don’t smoke. Stay active. If you’re under 45 and on birth control, talk to your doctor about your eye health, especially if you have other risk factors.

Regular eye exams are key. Many people with high blood pressure or diabetes don’t get their eyes checked often enough. A simple retinal scan can catch early signs of damage before vision loss happens.

Can retinal vein occlusion cause total blindness?

It rarely causes total blindness, but it can lead to severe vision loss if untreated. Central retinal vein occlusion (CRVO) is more likely to cause major vision loss than branch retinal vein occlusion (BRVO). With prompt treatment, many patients regain significant vision-up to 40% reach 20/40 or better. Without treatment, permanent damage to the retina can occur.

How long do eye injections for RVO last?

Anti-VEGF injections like Lucentis and Eylea work for about 4-6 weeks, which is why monthly shots are common at first. The Ozurdex steroid implant lasts 3-6 months. Newer delivery systems, like the Susvimo implant, are designed to release medication for 6 months or longer and are being tested for RVO.

Do eye injections hurt?

Most people feel only mild pressure or a brief sting. The eye is numbed with drops, and the procedure takes less than 10 minutes. The anxiety before the injection is often worse than the actual experience. Many clinics have staff trained to help patients relax during the process.

Is bevacizumab (Avastin) safe for RVO?

Yes. Although Avastin is not FDA-approved for eye use, it’s widely used off-label because it’s just as effective as brand-name drugs like Lucentis and costs far less. Studies show similar safety and effectiveness. Many hospitals and clinics use it, especially for patients with limited insurance coverage.

Can RVO happen in both eyes?

It’s rare but possible. About 5-10% of patients develop RVO in the second eye within 5 years, especially if they have ongoing risk factors like uncontrolled hypertension or blood disorders. Regular monitoring is important even after one eye is affected.

Saurabh Tiwari

December 3, 2025 AT 06:38Anthony Breakspear

December 4, 2025 AT 17:17ruiqing Jane

December 6, 2025 AT 00:59alaa ismail

December 6, 2025 AT 08:32John Morrow

December 6, 2025 AT 11:24Girish Padia

December 7, 2025 AT 14:40Carolyn Woodard

December 7, 2025 AT 23:33Kristen Yates

December 8, 2025 AT 04:39Michael Campbell

December 9, 2025 AT 20:16Fern Marder

December 11, 2025 AT 02:43Allan maniero

December 11, 2025 AT 22:44Victoria Graci

December 12, 2025 AT 04:00Zoe Bray

December 13, 2025 AT 16:40Chris Wallace

December 13, 2025 AT 23:12alaa ismail

December 15, 2025 AT 05:42