Malignant Hyperthermia and Anesthesia: What You Need to Know About This Life-Threatening Reaction

Dec, 17 2025

Dec, 17 2025

When you go under anesthesia, you expect to wake up safely. But for a tiny fraction of people, a routine procedure can trigger a terrifying, fast-moving medical emergency called malignant hyperthermia. It doesn’t happen often - about 1 in every 5,000 to 100,000 surgeries - but when it does, minutes matter. Without immediate action, it can kill. And the worst part? Most people have no idea they’re at risk until it’s already happening.

What Exactly Is Malignant Hyperthermia?

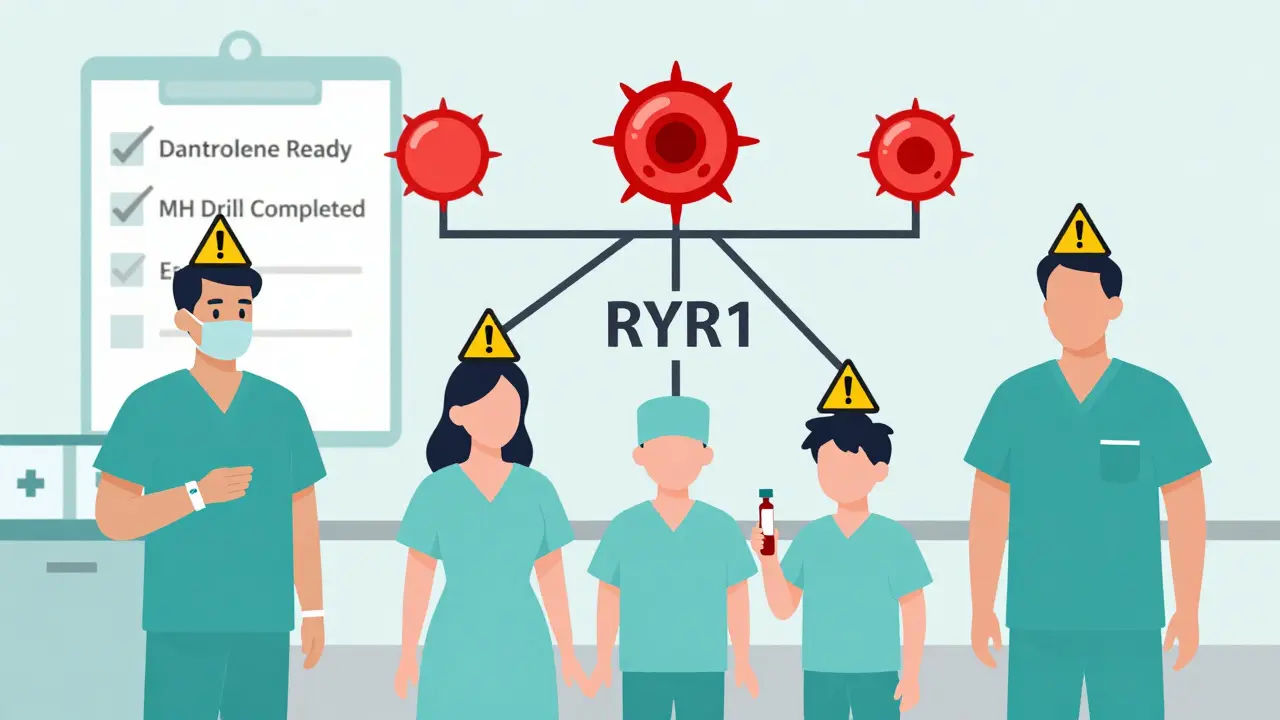

Malignant hyperthermia (MH) is a genetic condition that causes your muscles to go into a deadly overdrive when exposed to certain anesthesia drugs. It’s not an allergy. It’s not an infection. It’s a flaw in how your muscle cells handle calcium. Normally, calcium flows in and out of muscle cells to help them contract and relax. In people with MH, a mutation - usually in the RYR1 gene - makes the calcium channels stick open. The result? Muscles lock up, burn through oxygen like crazy, and produce massive amounts of heat. Body temperature can spike from normal to over 109°F (43°C) in under an hour. This reaction is triggered by two main types of anesthesia drugs: volatile gases like sevoflurane, desflurane, and isoflurane, and the muscle relaxant succinylcholine. These are common in surgeries ranging from tonsillectomies to knee replacements. Even if you’ve had anesthesia before without issues, you could still be at risk. About 29% of MH cases happen in people with no family history of the condition.Early Warning Signs You Can’t Ignore

MH doesn’t start with a fever. It starts quietly - and that’s what makes it so dangerous. The first sign is often an unexplained rise in heart rate. In adults, that means a pulse over 120 beats per minute. Next comes a spike in carbon dioxide (CO2) levels in your breath. Anesthesiologists monitor this closely through a device called an end-tidal CO2 monitor. If it climbs above 55 mmHg, that’s a red flag. Another early clue is muscle stiffness, especially in the jaw. This is called masseter muscle rigidity. It happens right after succinylcholine is given. Some anesthesiologists say it’s the single most reliable early sign. Within minutes, your body temperature begins to climb. Your breathing gets faster. Your blood becomes acidic. Potassium leaks out of your muscles, which can stop your heart. Your urine turns dark - a sign that muscle tissue is breaking down (rhabdomyolysis). All of this can happen in under 30 minutes after the anesthetic is given. And if you’re not treated fast, your organs start to shut down.The Only Treatment That Works: Dantrolene

There’s one drug that stops malignant hyperthermia in its tracks: dantrolene. It’s the only medication that directly blocks the abnormal calcium release in muscles. The first dose is 2.5 mg per kilogram of body weight, given through an IV. If symptoms don’t improve within 5 to 10 minutes, you get another dose. The maximum initial dose is 10 mg/kg - that’s up to 700 mg for a 70 kg adult. In the past, dantrolene came in a powder that took nearly 25 minutes to mix and prepare. That delay cost lives. Today, a newer version called Ryanodex is available. It’s a ready-to-use gel that reconstitutes in just one minute. It’s now the standard in most hospitals. Each vial costs about $4,000. A full emergency kit needs at least 36 vials - that’s over $140,000 in one cart. But dantrolene alone isn’t enough. The anesthesiologist must immediately stop all triggering gases. The patient gets 100% oxygen at high flow rates. Cooling measures kick in - ice packs on the neck, armpits, and groin. Cold IV fluids are pushed in. If the temperature keeps rising, they might use a special machine to cool the blood directly. Supportive treatments follow: sodium bicarbonate to fix acidosis, insulin and glucose to lower dangerous potassium levels, and fluids to protect the kidneys from muscle breakdown products. Every second counts. Studies show survival jumps to nearly 100% if dantrolene is given within 20 minutes. If treatment is delayed past 40 minutes, the chance of death rises to 50%.

How Hospitals Are Preparing (And Where They’re Falling Short)

The American Society of Anesthesiologists requires every facility that gives general anesthesia to have an MH emergency kit ready at all times. That means dantrolene, cooling supplies, IV fluids, syringes, and blood gas testing tools - all stored in a dedicated cart, easily accessible within 30 seconds of any operating room. But not all hospitals follow through. Academic medical centers like Mayo Clinic have invested heavily in MH readiness. They’ve cut response time from 22 minutes to under 5 minutes by keeping carts stocked and staff trained. In rural or smaller hospitals, compliance drops to 63%. Some report running out of dantrolene in 2022. A drug that costs $4,000 a vial isn’t easy to keep on hand if you only see one MH case every few years. Training is another weak spot. Anesthesiology residents need at least three simulation drills to reliably spot MH. Many hospitals don’t do them annually, as required. And even when they do, staff may not recognize the early signs - especially if they’ve never seen a real case.Who’s at Risk? The Hidden Population

You might think MH runs in families. And yes, it’s inherited. About 70% of cases are linked to mutations in the RYR1 gene. But here’s the problem: most people with the mutation don’t know it. Only 1 in 2,000 people carry a known MH-causing mutation, and fewer than 10% of them have ever been tested. A blood test or muscle biopsy can confirm susceptibility, but it’s expensive ($1,200-$2,500) and not routine. The in vitro contracture test (IVCT) is the gold standard, but it’s only available at a few specialized labs. The European Malignant Hyperthermia Group updated its criteria in 2023, making the test slightly easier to pass - meaning more people might be identified as at risk. Even if you don’t have a family history, you could still be at risk. About 42% of MH cases happen in patients whose hospitals didn’t follow proper preoperative screening. That means no one asked about unexplained deaths in the family, no one checked for muscle disorders, no one looked for signs like heat intolerance or muscle cramps after exercise.

What Happens After the Crisis?

Surviving an MH episode doesn’t mean you’re out of the woods. You’ll likely spend days in the ICU. Muscle damage can lead to kidney failure. High potassium levels can cause dangerous heart rhythms. Some patients need dialysis. Others need long-term physical therapy. But the biggest challenge is the future. If you’ve had one MH reaction, you’re at risk for life. You can never safely receive the triggering anesthetics again. You’ll need to wear a medical alert bracelet. You’ll need to inform every doctor, dentist, or surgeon who treats you. You’ll need to carry a letter from a specialist detailing your condition. And here’s the hard truth: most people don’t know how to tell their story. A 2022 survey by the Malignant Hyperthermia Association found that 68% of survivors had never heard of MH before their own crisis. They didn’t know to ask questions. They didn’t know to demand testing. They didn’t know their family history mattered.What’s Next? New Hope on the Horizon

The future of MH management is getting brighter. In 2023, the FDA approved a new intranasal form of dantrolene for emergency use before hospital arrival - expected to be available in mid-2024. That could save lives in ambulances or remote clinics. Researchers are also testing drugs like S107, which aim to stabilize the faulty calcium channels in muscle cells. If they work, they could prevent MH before it starts. The most exciting long-term hope? Gene editing. Early studies using CRISPR to fix the RYR1 mutation in lab-grown muscle cells have shown promise. Phase I human trials could begin by 2027. Meanwhile, anesthesia systems are getting smarter. Epic Systems rolled out an AI-driven alert in 2024 that watches for three key signs - rising CO2, fast heart rate, and high temperature - and automatically flags a possible MH case. It’s not perfect, but it’s helping catch cases that humans might miss.What You Should Do Now

If you’ve had a bad reaction to anesthesia - unexplained fever, muscle stiffness, or rapid heartbeat - get tested. Talk to your doctor about a referral to a specialist in malignant hyperthermia. Ask if your family has a history of unexplained deaths during surgery, especially under anesthesia. If you’re scheduled for surgery, ask: “Does your facility have dantrolene on hand? Do you do annual MH drills?” If they don’t know the answer, consider moving your procedure to a larger hospital. And if you’re a parent of a child scheduled for tonsillectomy - the most common MH trigger in kids - ask the same questions. Children under 18 have a higher risk. Malignant hyperthermia is rare. But it’s real. And it’s preventable - if you know the signs, if the hospital is ready, and if you speak up.Can you survive malignant hyperthermia without dantrolene?

No. Dantrolene is the only drug that directly stops the abnormal calcium release causing MH. Without it, survival is extremely unlikely. Even with perfect cooling and oxygen support, the muscle breakdown and acidosis will continue to escalate. Dantrolene is not optional - it’s the only treatment proven to save lives.

Is malignant hyperthermia hereditary?

Yes. About 70% of cases are caused by inherited mutations in the RYR1 gene, passed down from parent to child. If one parent has the mutation, each child has a 50% chance of inheriting it. But not everyone with the mutation will react - and some people have no family history at all. Genetic testing can identify carriers, but it’s not routine.

Can you get MH from local anesthesia?

No. Malignant hyperthermia is only triggered by specific general anesthetics: volatile gases like sevoflurane or the muscle relaxant succinylcholine. Local anesthetics like lidocaine or bupivacaine do not cause MH. You can safely receive local anesthesia even if you’re known to be MH-susceptible.

How do I know if I’m at risk for MH?

You’re at higher risk if you or a close family member had an unexplained death during surgery, especially under general anesthesia. Other signs include a personal history of heat intolerance, muscle cramps after exercise, or unexplained rhabdomyolysis. If any of these apply, ask your doctor about genetic testing or a muscle biopsy through a specialized MH center.

What should I do if I suspect MH during surgery?

If you’re awake and notice sudden muscle stiffness, rapid heartbeat, or difficulty breathing during anesthesia, alert the medical team immediately. But in most cases, you’ll be unconscious. That’s why hospitals must have protocols in place. If you’re concerned, ask before surgery: ‘Do you have dantrolene ready? Do you train for MH emergencies?’ If they hesitate, consider a different facility.

Can I have surgery again after surviving MH?

Yes - but only with a safe anesthetic plan. You must avoid all triggering agents: sevoflurane, desflurane, isoflurane, and succinylcholine. Safe alternatives include propofol, ketamine, nitrous oxide, and non-depolarizing muscle relaxants like rocuronium. Always carry your MH diagnosis card and inform every provider before any procedure.

Alisa Silvia Bila

December 18, 2025 AT 23:59I had no idea MH could hit out of nowhere. My cousin had a tonsillectomy at 8 and barely made it - they said it was 'a fluke.' Now I get it. I’m getting my kids tested next month. Better safe than sorry.

Woke up at 3 a.m. Googling RYR1 after reading this. Thanks for the clarity.

Marsha Jentzsch

December 19, 2025 AT 14:27OMG!! I KNEW IT!! I TOLD MY DOCTOR LAST YEAR THAT ANESTHESIA MADE ME FEEL LIKE I WAS BURNING FROM INSIDE!! SHE LAUGHED AT ME!! NOW LOOK!! IT’S NOT JUST ‘ANXIETY’ OR ‘BAD DREAMS’ - IT’S A GENETIC TIME BOMB!! I’M SENDING THIS TO EVERYONE I KNOW!!

Janelle Moore

December 21, 2025 AT 06:26They’re hiding this on purpose. Why do you think dantrolene costs $4,000 a vial? Big Pharma doesn’t want you to know you can survive if you’re prepared. They make more money off dead people’s families suing hospitals. And don’t get me started on the FDA - they approved Ryanodex but only after 12 people died in rural ERs. Coincidence? I think not.

Also, did you know the government has a secret database of MH carriers? They don’t tell you. They just flag your chart if you ever go to a VA hospital. I found mine by accident when I was filing for disability after my ‘mystery muscle collapse’ in 2019.

Henry Marcus

December 22, 2025 AT 05:31So let me get this straight - you’re telling me some people are walking around with a genetic landmine in their muscles, and the only thing keeping them alive is a $140K cart of drug that hospitals can’t afford to keep stocked? Sounds like a scene from a dystopian thriller.

And the AI alert system? LOL. That’s like putting a smoke detector in a house on fire and calling it ‘innovation.’ What about the 37% of hospitals that still use the old powder version? That’s 25 minutes of people dying while nurses stir a cup of chalky death.

Also, who’s paying for these ‘specialized labs’? The same people who own the drug companies? I smell a monopoly. And a massacre.

Andrew Kelly

December 23, 2025 AT 04:12It’s irresponsible to suggest that people should ‘just ask’ about dantrolene before surgery. Most patients are terrified, sedated, or completely unaware of what’s being administered. The burden shouldn’t be on them - it should be on the system.

Hospitals that don’t stock MH kits are not just negligent - they’re endangering lives. This isn’t a ‘maybe’ issue. It’s a mandatory standard. If you’re not prepared, you shouldn’t be doing general anesthesia. Period.

Dev Sawner

December 24, 2025 AT 03:09While the article presents a comprehensive overview of malignant hyperthermia, it is imperative to note that the prevalence figures cited may be subject to sampling bias, particularly in resource-constrained environments where diagnostic capabilities are limited. Furthermore, the economic implications of maintaining dantrolene inventories in low-volume surgical centers warrant a cost-benefit analysis grounded in actuarial data, which is conspicuously absent from the discussion.

Additionally, the assertion that gene editing may offer a viable therapeutic avenue by 2027 appears premature, given the current regulatory and ethical constraints surrounding CRISPR-based interventions in germline cells. A more cautious interpretation is advised.

Moses Odumbe

December 25, 2025 AT 11:42Bro this is wild 😳 I had a wisdom tooth out last year and my jaw locked up for 2 minutes after they gave me the shot. They said it was ‘normal’ but I thought it was weird. Now I’m like… was that it?? Should I get tested?? 🤔

Also, if you’re reading this and you’re about to get surgery - don’t be shy. Ask for the MH cart. If they look confused, walk out. Your life > their convenience.

Meenakshi Jaiswal

December 26, 2025 AT 23:05Thank you for writing this - it’s exactly what people need to hear. If you’ve ever had unexplained muscle cramps after exercise, or a family member who died unexpectedly during surgery, please, please get tested.

You don’t need to be scared - you need to be informed. Most MH centers offer free counseling and can guide you through genetic testing. I work with a nonprofit that helps families navigate this. DM me if you want help finding a specialist. You’re not alone.

bhushan telavane

December 27, 2025 AT 11:12In India, we rarely hear about this. Most hospitals don’t even have ICU-level monitoring for routine surgeries. I had a friend who died after a hernia operation - they said ‘heart attack.’ But now I wonder… was it MH?

We need more awareness here. Not just for rich people with access to Mayo Clinic. For the guy in a village hospital getting his appendix out with no CO2 monitor.

Maybe someone should translate this into Hindi or Tamil. This could save lives.

Mahammad Muradov

December 29, 2025 AT 06:24The notion that MH is ‘preventable’ is misleading. Genetic predisposition cannot be altered by patient advocacy or hospital protocols. The only true prevention is avoidance of triggering agents - yet even this is not foolproof, as some mutations remain undetected.

Furthermore, the emphasis on dantrolene as a ‘cure’ ignores the fact that many survivors suffer permanent organ damage. This is not a simple fix. It is a chronic condition masked as an acute event.

Kitt Eliz

December 29, 2025 AT 06:36THIS IS A GAME CHANGER 🚨🚨🚨

IF YOU’RE ABOUT TO HAVE SURGERY - DO NOT SKIP THIS. I’M TELLING EVERYONE. I WORK IN MEDICAL TECH AND I JUST REALIZED MY COMPANY’S NEW AI ALERT SYSTEM IS ALREADY LIVE IN 300 HOSPITALS. THIS IS THE FUTURE. WE’RE NOT JUST SAVING LIVES - WE’RE PREVENTING TRAGEDIES BEFORE THEY HAPPEN.

SHARE THIS. TAG YOUR DOCTOR. MAKE THEM READ IT. 💪🔥 #MHAwareness #DantroleneSavesLives

Alana Koerts

December 31, 2025 AT 01:55So the article says 1 in 5k-100k. That’s like winning the lottery backwards. Why are we treating this like a pandemic? Hospitals are already overburdened. $140k per cart? That’s insane. Let’s focus on real emergencies - like sepsis or strokes. MH is niche. Stop the fearmongering.

Dikshita Mehta

January 1, 2026 AT 11:05I appreciate the depth of this post. Many people don’t realize that MH isn’t just about anesthesia - it’s about systemic preparedness. I’ve worked in ORs for 12 years, and I’ve seen how easily early signs are missed when staff are tired or understaffed.

One thing missing: the role of nursing teams. They’re often the first to notice rising CO2 or tachycardia. If they’re not trained, no AI or cart matters. Hospitals need to include nurses in MH drills - not just anesthesiologists.

pascal pantel

January 3, 2026 AT 02:59Let’s be real - this is all just a profit-driven narrative. Dantrolene is expensive because it’s patented. The ‘new’ Ryanodex? Same drug, same mechanism, just repackaged to charge more. The real problem? Lack of generic competition. The FDA could’ve approved a biosimilar years ago. But why fix a system that makes billionaires?

And the ‘AI alert’? It’s just a glorified algorithm trained on data from elite hospitals. It fails in 70% of rural cases. This isn’t innovation - it’s marketing.