Heparin-Induced Thrombocytopenia: What You Need to Know About This Rare but Dangerous Side Effect

Dec, 20 2025

Dec, 20 2025

HIT Probability Calculator

HIT Probability Assessment

The 4Ts score is a clinical tool to estimate the likelihood of Heparin-Induced Thrombocytopenia. Enter values based on patient data to calculate probability.

Probability Results

Disclaimer: This tool is for educational purposes only. Always correlate with clinical judgment and laboratory testing.

When you're given heparin after surgery or for a blood clot, you expect it to protect you-not hurt you. But in about 1 in 20 people who get unfractionated heparin for more than four days, something dangerous happens: their platelets crash, and their blood starts clotting in places it shouldn't. This isn't a typo or a mistake. It's heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, or HIT. A rare side effect, yes-but when it strikes, it can turn a routine treatment into a life-or-death emergency.

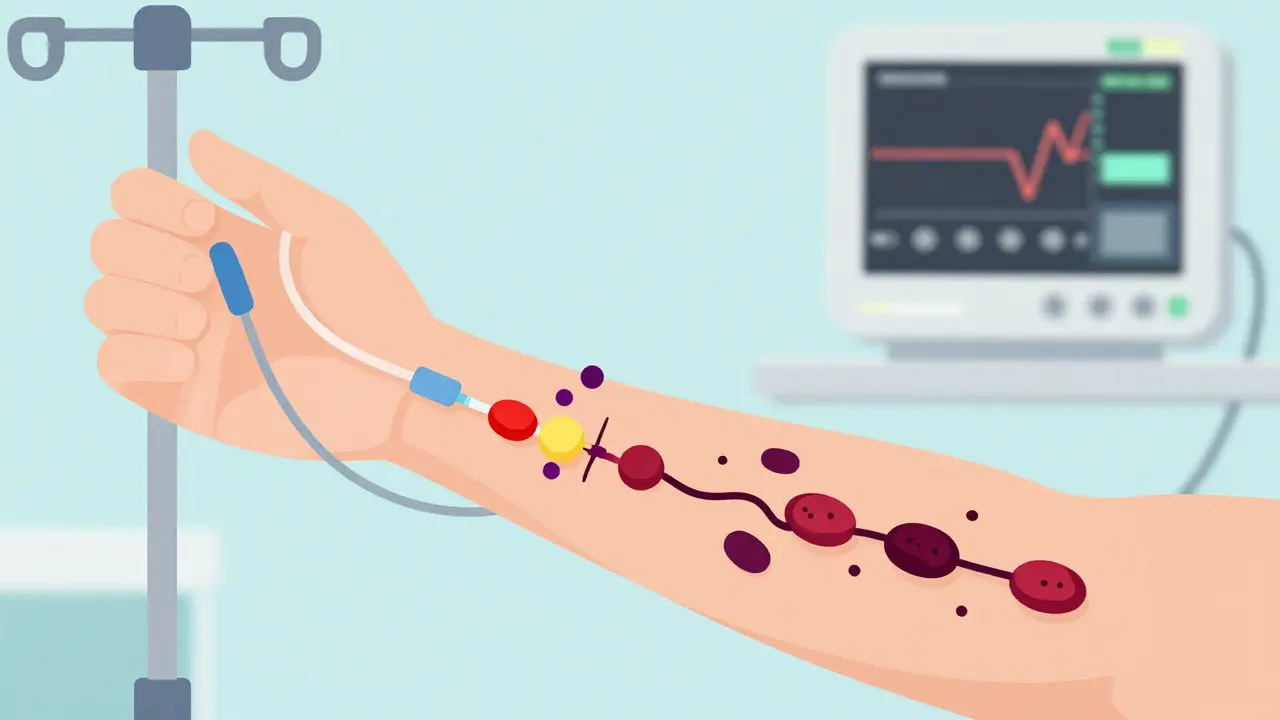

How Heparin, a Blood Thinner, Starts Making Clots

Heparin has been used since the 1930s to prevent dangerous clots. It works by boosting a natural anticoagulant in your blood. But in some people, the body mistakes heparin for a threat. It creates antibodies that latch onto a protein called platelet factor 4 (PF4), which naturally binds to heparin. These antibody complexes then stick to platelets, triggering them to activate and clump together. The result? Fewer platelets in circulation (thrombocytopenia) and a flood of clotting signals (hypercoagulability).This isn't just low platelets. It's low platelets + new clots. That combination is called Heparin-Induced Thrombocytopenia and Thrombosis, or HITT. About half of all HIT cases turn into HITT. And that’s when things get serious.

When Does HIT Show Up? Timing Matters

HIT doesn’t happen right away. If you’ve never been exposed to heparin before, symptoms usually appear between days 5 and 14 of treatment. That’s why checking platelet counts every 2-3 days starting on day 4 is standard practice in hospitals. But here’s the twist: if you’ve had heparin in the last 100 days-even just a flush in a catheter-you can develop HIT in as little as 24 to 72 hours. Your body already has the antibodies waiting.Unfractionated heparin (the older, more commonly used type in hospitals) carries a 3-5% risk. Low molecular weight heparin (like enoxaparin), often used for outpatient care, is safer-but still risky, with a 1-2% chance. Even a heparin-coated catheter or a tiny heparin flush can trigger it. That’s why doctors now check for HIT even when heparin is given in small doses.

What Does HIT Feel Like? The Warning Signs

Most people don’t notice their platelets dropping. But the clots? Those are impossible to ignore.- Sudden swelling, warmth, or pain in one leg-often a deep vein thrombosis (DVT). This happens in 25-30% of cases.

- Shortness of breath, chest pain, rapid heartbeat-signs of a pulmonary embolism (PE). Seen in 15-20% of HIT patients.

- Dark patches or blackening skin around injection sites. This isn’t just bruising. It’s skin necrosis, and it’s a red flag.

- Cold, blue fingers or toes. That’s acral ischemia-clots blocking blood flow to extremities.

- Fever, chills, dizziness, or anxiety. These are less specific but still common.

One patient described waking up with a sharp pain in her chest and a leg that felt like it was on fire. She’d been on heparin for seven days after knee surgery. Her platelets had dropped by 60%. She didn’t know what was happening-until the ER team recognized the pattern.

Who’s Most at Risk?

Not everyone gets HIT. But some groups are far more vulnerable:- Women: 1.5 to 2 times more likely than men.

- People over 40: Risk doubles or triples compared to younger patients.

- Orthopedic surgery patients: Especially those having hip or knee replacements. Up to 10% develop HIT here.

- Those with prior heparin exposure: Even if it was months ago.

- Patients on unfractionated heparin for more than 10 days: Risk jumps to 5-10%.

Cardiac surgery patients are also at higher risk, though not as high as orthopedic. Medical patients (like those in ICU with blood clots) have lower rates, around 1-3%. But that doesn’t mean they’re safe.

How Do Doctors Diagnose HIT?

You can’t just look at a platelet count and say, “That’s HIT.” Many things cause low platelets-drugs, infections, autoimmune disorders. So doctors use a tool called the 4Ts score:- Thrombocytopenia: How much did platelets drop? A drop of 50% or more counts as high.

- Timing: Did the drop happen between days 5-14? Or within 1-3 days after recent heparin exposure?

- Thrombosis: Are there new clots? Or skin necrosis?

- Other causes: Are there other reasons for low platelets? If yes, subtract points.

A score of 6-8 means high probability. 4-5 is intermediate. 0-3 is low. Only if the score is high or intermediate do doctors order lab tests.

The first lab test is an immunoassay-it checks for PF4/heparin antibodies. It’s sensitive (95-98%) but not specific. Many people test positive without having HIT. So the second test, the serotonin release assay or heparin-induced platelet activation test, is the gold standard. It’s 99% specific. But it’s slow, expensive, and not available everywhere. That’s why the 4Ts score is so important-it prevents overtesting and unnecessary treatment.

What Happens If HIT Is Left Untreated?

Untreated HIT with thrombosis has a 20-30% death rate. That’s not a small risk. Survivors often face amputations (5-10% of severe cases), chronic pain, or permanent organ damage. A clot in the brain can cause a stroke. A clot in the kidney can lead to renal failure. Even if you survive, your life changes.One patient, a 52-year-old man after heart surgery, developed skin necrosis and a pulmonary embolism. He lost part of his finger. He now takes anticoagulants for life and avoids any heparin product-even dental cleanings require special planning.

How Is HIT Treated? Stop Heparin. Now.

The first rule: Stop all heparin immediately. That includes heparin flushes, heparin-coated catheters, even heparin locks on IV lines. Continuing heparin makes things worse.You need a different anticoagulant-something that doesn’t interact with PF4. The main options:

- Argatroban: Given by IV. Used when liver function is poor. Dose adjusted based on blood tests.

- Bivalirudin: Preferred during cardiac surgery or procedures.

- Fondaparinux: A once-daily shot. Now recommended as first-line for non-life-threatening cases because it’s effective and easy to use.

- Danaparoid: Available in some countries, not the U.S.

Never start warfarin alone during acute HIT. Warfarin can cause skin necrosis in HIT patients-worse than the original problem. Warfarin can only be added after platelets recover above 150,000/μL and you’ve been on a safe anticoagulant for at least five days.

How Long Do You Need Treatment?

If you had HIT without clots, you’ll typically need anticoagulation for 1-3 months. If you had HITT (clots), you’ll need 3-6 months. If you’ve had a second clot or a history of clots, you might need it for life. The goal is to prevent new clots while your body clears the antibodies.What About Future Heparin Use?

Once you’ve had HIT, you’re at risk for life. Even if you’re told you’re “cured,” the antibodies can linger for years. If you ever need surgery, a catheter, or even a blood test with a heparin-coated tube, tell every doctor you’ve had HIT. Avoid all heparin products. Alternative anticoagulants like fondaparinux or direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) may be used-but only under strict supervision.Why Is HIT Still a Problem in 2025?

Heparin is given to over a million patients every year in the U.S. alone. That means 50,000 to 100,000 cases of HIT happen annually. The cost? Up to $50,000 extra per HITT case. Hospitals are now required to track HIT rates as part of patient safety goals.Despite decades of research, we still don’t fully understand why some people develop antibodies and others don’t. New tests are coming-like PF4-only assays that could cut false positives. Researchers are even testing drugs that block PF4-heparin binding before antibodies form. But for now, the best defense is awareness.

What Should You Do If You’re on Heparin?

If you’re receiving heparin:- Know the signs: swelling, pain, skin changes, trouble breathing.

- Ask: “Am I being monitored for platelet drops?”

- Speak up if you feel something’s wrong-even if it’s “just” anxiety or dizziness.

- Keep a personal health record: Note when you got heparin, for how long, and any reactions.

If you’ve had HIT before, carry a medical alert card or wear a bracelet. Make sure your primary care doctor and any specialist knows your history. Don’t assume it’s “not a big deal.” It is.

Can HIT happen with low-dose heparin, like a flush?

Yes. About 15-20% of HIT cases are triggered by heparin flushes, heparin-coated catheters, or even small doses used to keep IV lines open. You don’t need a full treatment course. Any exposure can be enough, especially if you’ve had heparin in the past 100 days.

Is HIT the same as DIC or ITP?

No. Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) involves widespread clotting and bleeding due to severe illness like sepsis. Immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) is when antibodies destroy platelets without causing clots. HIT is unique: it causes both low platelets AND dangerous clots. The mechanism is different, and so is the treatment.

Can I ever use heparin again after having HIT?

It’s strongly discouraged. Even years later, the antibodies can still be present. Re-exposure can trigger a rapid, severe reaction within hours. If absolutely necessary-like during emergency heart surgery-specialized testing and expert oversight are required. Most doctors will avoid heparin entirely.

Do all patients with low platelets on heparin have HIT?

No. About 1 in 3 patients on heparin have a mild, temporary drop in platelets that’s harmless-called Type I HIT. It happens within 24-48 hours, doesn’t cause clots, and resolves on its own. Only Type II HIT, the immune-driven form, is dangerous and needs treatment.

How long do HIT antibodies last?

In most people, antibodies fade within 3-6 months. But in up to 20% of cases, they can remain detectable for years. That’s why lifelong avoidance of heparin is recommended-even if you feel fine. A single exposure can restart the cycle.

Cameron Hoover

December 20, 2025 AT 14:58Just had a friend go through this after knee surgery. She didn’t know anything about HIT until her leg turned into a fire hydrant. Now she carries a medical alert card and makes sure every doctor knows. If you’re on heparin, don’t wait for symptoms-ask for platelet checks. Seriously.

Life’s too short to assume ‘it’s probably fine.’

Stacey Smith

December 22, 2025 AT 06:32Heparin is dangerous and the medical system ignores it until someone loses a limb. This isn’t rare-it’s systemic negligence.

Teya Derksen Friesen

December 23, 2025 AT 09:41It is both fascinating and profoundly concerning that a therapeutic agent, so widely employed for its anticoagulant properties, can paradoxically induce a prothrombotic state in susceptible individuals. The immunological mechanism involving PF4 antibodies represents a compelling example of molecular mimicry and immune dysregulation. One must commend the clinical diligence required to differentiate Type I from Type II HIT, as misdiagnosis carries catastrophic consequences.

It is imperative that healthcare institutions implement mandatory platelet monitoring protocols for all patients receiving heparin beyond 48 hours.

Sandy Crux

December 24, 2025 AT 01:47Of course, the article conveniently omits the fact that heparin is a byproduct of pig intestines-so it’s not just ‘rare,’ it’s inherently ‘unnatural.’ And now we’re surprised when the body rejects it? What did we expect? Synthetic alternatives exist, but Big Pharma profits from animal-derived anticoagulants. Also, the 4Ts score? A band-aid on a bullet wound. They still miss 12% of cases. And don’t get me started on fondaparinux-it’s just heparin with a better PR team.

Hannah Taylor

December 24, 2025 AT 06:01hmmmm… i think this is all a lie. they’re using heparin to control our platelets so the gov can track us through our blood. did you know the catheters have microchips? i read it on a forum. also, my cousin’s dog got heparin and now it barks in morse code. the real danger is they don’t want you to know you can just take turmeric and lemon water. #heparinshill

Jason Silva

December 24, 2025 AT 10:36Bro, I got HIT after a simple stent. Lost 3 days of my life in ICU. They didn’t even check my platelets until I turned blue. 😡

DOCTORS ARE LAZY. If you’re on heparin, demand a CBC every 48 hours. No excuses. 🚨💉

Also, if you’ve had it once? NEVER AGAIN. I’ve told 12 people since. Spread the word.

Meina Taiwo

December 25, 2025 AT 16:24Key point: HIT can occur even after a single heparin flush. Many clinicians overlook this. Always ask about prior exposure. Early detection saves limbs.

Swapneel Mehta

December 26, 2025 AT 23:45Interesting how the body’s immune system can turn a life-saving drug into a threat. I wonder if genetic factors play a bigger role than we think. Maybe someday we’ll screen for PF4 sensitivity before surgery. Would be a game-changer.

Ben Warren

December 28, 2025 AT 03:41It is regrettably apparent that the prevailing clinical paradigm remains dangerously reactive rather than proactively preventive. The absence of universal genomic screening for PF4 antibody predisposition constitutes a glaring omission in modern medical practice. Furthermore, the continued reliance on unfractionated heparin in high-risk surgical populations-despite the availability of safer alternatives-is not merely negligent; it is an affront to the ethical obligations of beneficence and non-maleficence. One cannot help but question the institutional inertia that permits such preventable morbidity to persist in the 21st century.

Theo Newbold

December 28, 2025 AT 17:04They say ‘1 in 20’ but they never mention how many of those were already on multiple anticoagulants or had sepsis. The data is contaminated. Also, fondaparinux? It’s just a heparin analog with a longer half-life. Same mechanism, different brand name. You’re not solving the problem-you’re just delaying it.

Michael Ochieng

December 29, 2025 AT 13:33As someone from Kenya, I’ve seen HIT cases in rural hospitals where they don’t even have platelet counters. The fact that this is even a discussion in the U.S. shows how far we’ve come-but also how far we still have to go. Awareness needs to be global. Not just in fancy hospitals with 4Ts scores.

Erika Putri Aldana

December 31, 2025 AT 12:40so like… we’re all just lab rats for big pharma? heparin’s been around since the 30s and now they’re acting like it’s new? i’m just here for the drama. also, why do they always make it sound so serious? it’s just blood. 🤷♀️