ACE Inhibitors and Potassium-Sparing Diuretics: Understanding the Hyperkalemia Risk

Nov, 15 2025

Nov, 15 2025

Hyperkalemia Risk Calculator

Your Risk Factors

Your Risk Assessment

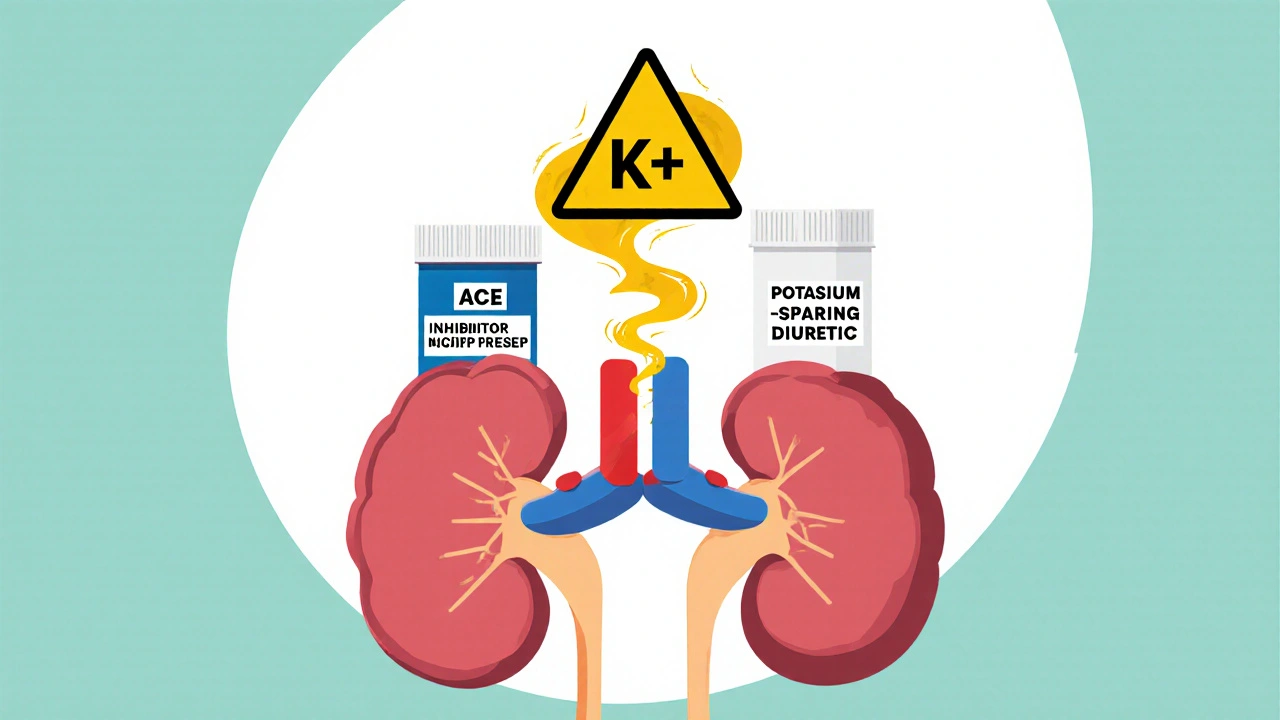

When you take an ACE inhibitor and a potassium-sparing diuretic together, your body can’t get rid of potassium the way it should. That might sound harmless-after all, potassium is essential for your heart and muscles. But too much of it? That’s when things turn dangerous. Serum potassium above 5.0 mmol/L is considered high. Above 6.0 mmol/L? That’s a medical emergency. You could develop irregular heart rhythms, muscle weakness, or even sudden cardiac arrest. And this isn’t rare. In fact, up to 18% of patients on this combo develop hyperkalemia, especially if they have kidney problems, diabetes, or heart failure.

How These Drugs Work Together-And Why That’s a Problem

ACE inhibitors like lisinopril, enalapril, or ramipril lower blood pressure by blocking the enzyme that turns angiotensin I into angiotensin II. Less angiotensin II means less aldosterone, a hormone that tells your kidneys to dump potassium into your urine. So naturally, potassium builds up.

Now add a potassium-sparing diuretic-spironolactone, eplerenone, amiloride, or triamterene. These drugs don’t make you pee out more potassium; they actually stop your kidneys from getting rid of it. Spironolactone and eplerenone block aldosterone receptors. Amiloride and triamterene shut down sodium channels in the kidney tubules, which indirectly traps potassium inside your body.

Put them together, and you’ve got a double hit: one drug reduces potassium excretion by cutting aldosterone, the other blocks the final step where potassium leaves your body. The result? Potassium piles up. This isn’t just theory. A 1998 study of over 1,800 patients found that 11% of those on ACE inhibitors alone developed high potassium. When you add a potassium-sparing diuretic, that number jumps to nearly 20%.

Who’s Most at Risk?

Not everyone on this combo will get hyperkalemia. But some people are sitting on a ticking clock. The Cleveland Clinic has a simple risk score for this:

- eGFR below 60 mL/min/1.73m² → 2 points

- Baseline potassium above 4.5 mmol/L → 2 points

- Diabetes → 1 point

- Heart failure → 1 point

- Taking a potassium-sparing diuretic → 2 points

If you score 4 or higher, you’re high risk. That means you’re more likely to have kidney damage, older age, or other conditions that slow potassium clearance. The REIN study showed that in patients with chronic kidney disease, adding spironolactone to an ACE inhibitor raised hyperkalemia rates from 4.2% to 18.7%. That’s a fourfold increase.

And here’s something most people don’t realize: hyperkalemia doesn’t wait. About 78% of cases happen within the first three months of starting the combo. The peak? Weeks 4 to 6. That’s when you’re most vulnerable.

What Happens When Potassium Gets Too High?

High potassium doesn’t always cause symptoms. That’s the scary part. You might feel fine until your heart starts misfiring. On an ECG, you might see tall, peaked T-waves, widened QRS complexes, or even a flat P-wave. In severe cases, the heart rhythm can turn into ventricular fibrillation or asystole-both fatal without immediate treatment.

But even mild hyperkalemia has consequences. A 2016 study found that when doctors spot high potassium, they stop the RAAS inhibitors (like ACE inhibitors) in 43% of cases. That’s a problem because these drugs cut death risk in heart failure by 23% and after a heart attack by 26%. Stopping them because of potassium can actually hurt you more in the long run.

What Should You Do? Monitoring and Management

The good news? Hyperkalemia from this combo is preventable-if you monitor it right.

Here’s what the guidelines say:

- If your eGFR is between 30 and 60: Check potassium within one week of starting the combo, then monthly for 3 months, then every 3 months.

- If your eGFR is below 30: Check weekly at first, then every 2 weeks.

- If you have diabetes or heart failure: Start at half the usual dose of either drug and check potassium at 1, 2, and 4 weeks.

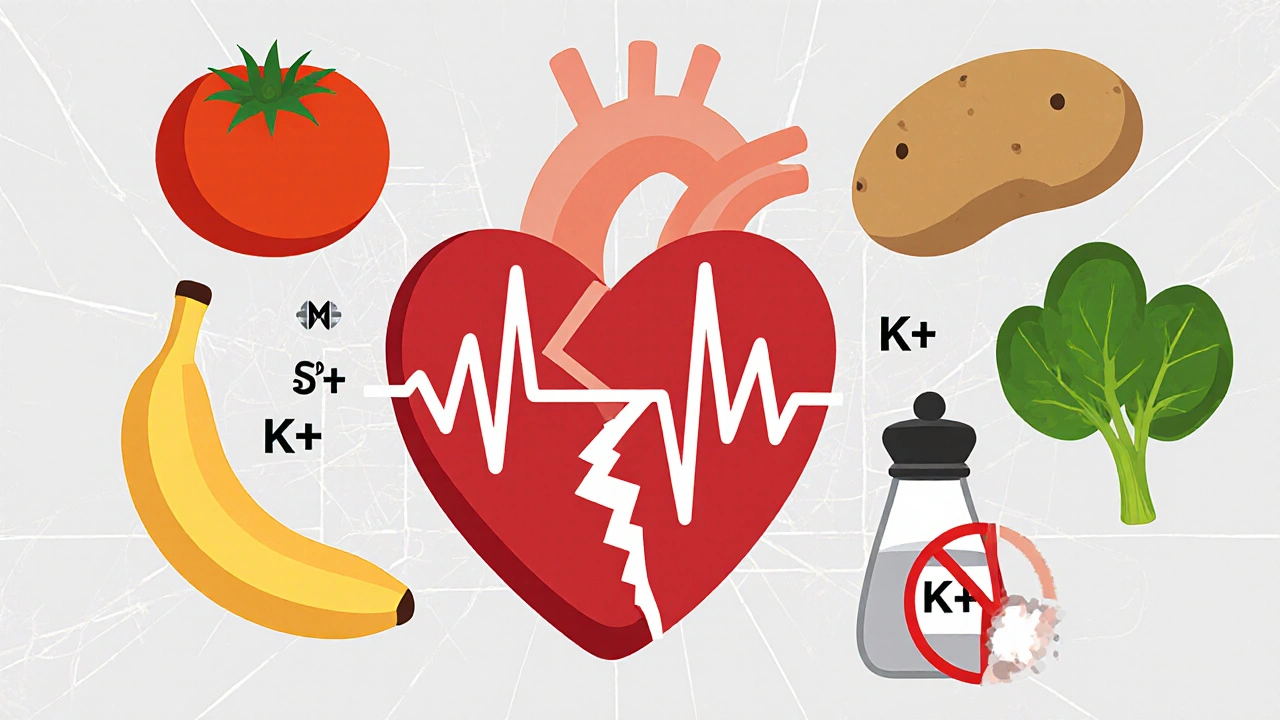

And if potassium climbs above 5.0 mmol/L? Don’t panic. First, look at your diet. Are you eating bananas, oranges, potatoes, tomatoes, spinach, or salt substitutes? Those are loaded with potassium. Cutting back can drop your levels by 0.3 to 0.6 mmol/L. Most people don’t realize that processed foods now contain potassium additives-some have up to 2,000 mg extra per day.

If diet alone doesn’t help, your doctor might:

- Switch you to a thiazide or loop diuretic (like hydrochlorothiazide or furosemide), which help flush out potassium.

- Lower the dose of your ACE inhibitor by 50% and retest in 1-2 weeks.

- Add sodium bicarbonate if you have metabolic acidosis-it can reduce recurrence by 47%.

But here’s the reality: only 32% of patients with hyperkalemia get dietary counseling. And only 18% of those who could benefit from sodium bicarbonate actually get it.

New Tools to Keep You Safe

There’s been a breakthrough in the last few years. Two new drugs-patiromer (Veltassa) and sodium zirconium cyclosilicate (Lokelma)-bind potassium in your gut so it leaves your body in your stool, not your urine. Clinical trials show they drop potassium by 0.8 to 1.2 mmol/L within 48 hours. And crucially, they let you keep taking your ACE inhibitor and spironolactone. In one study, 89% of patients who couldn’t tolerate the combo before were able to stay on it after starting one of these binders.

Another promising option? SGLT2 inhibitors like dapagliflozin. Originally for diabetes, they’ve been shown to cut hyperkalemia risk by 32% in patients with kidney disease on RAAS blockers. Now, doctors are starting to use them as a triple therapy: ACE inhibitor + potassium-sparing diuretic + SGLT2 inhibitor. It’s not standard yet, but it’s gaining traction.

And there’s tech on the horizon. Smartphone apps that track your potassium intake are reducing hyperkalemia episodes by 27% compared to standard care. New point-of-care devices that check potassium levels with a finger prick are in late-stage trials. Within a few years, you might be able to test your potassium at home, just like a blood sugar monitor.

What You Can Do Right Now

If you’re on an ACE inhibitor and a potassium-sparing diuretic:

- Ask your doctor for your latest eGFR and potassium level. Write them down.

- Check your diet. Avoid bananas, oranges, potatoes, tomatoes, spinach, and salt substitutes like No-Salt or Lite Salt.

- Read food labels. Look for “potassium chloride” or “potassium phosphate” in ingredients-that’s hidden potassium.

- Don’t skip your follow-up blood tests. Even if you feel fine.

- If your potassium is high, don’t assume you have to stop your heart medication. Ask about potassium binders or switching to a different diuretic.

Hyperkalemia isn’t a reason to quit your meds. It’s a signal to adjust them-safely, smartly, and with support. The goal isn’t to avoid these drugs. It’s to use them without risking your life.

When to Call Your Doctor

Call immediately if you experience:

- Chest pain or palpitations

- Unexplained muscle weakness or numbness

- Difficulty breathing

- Feeling unusually tired or dizzy

And if your potassium level is above 5.5 mmol/L, schedule a follow-up within 48 hours-even if you feel okay. Delayed action can be deadly.

Can I take ACE inhibitors and potassium-sparing diuretics together safely?

Yes-but only under close medical supervision. The combination increases hyperkalemia risk significantly, especially if you have kidney disease, diabetes, or heart failure. Your doctor should check your potassium levels within 1 week of starting the combo, then regularly. Never start or stop these medications on your own.

What foods should I avoid if I’m on these drugs?

Avoid high-potassium foods like bananas, oranges, potatoes, tomatoes, spinach, avocados, beans, and salt substitutes (No-Salt, Lite Salt). Also watch for potassium additives in processed foods-look for potassium chloride, potassium phosphate, or potassium lactate on labels. Cutting back can lower your serum potassium by 0.3-0.6 mmol/L.

Can I switch to a different blood pressure medication to avoid this risk?

Possibly. Angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) carry a slightly lower risk of hyperkalemia than ACE inhibitors, but the difference is small. Thiazide or loop diuretics (like hydrochlorothiazide or furosemide) are safer choices if you need a diuretic. Talk to your doctor about alternatives based on your heart and kidney health.

How often should my potassium be checked?

It depends on your risk. If your eGFR is above 60 and you have no diabetes or heart failure, testing every 6 months may be enough. If you’re high risk (eGFR below 60, diabetes, heart failure), check within 1 week of starting the combo, then at 2 and 4 weeks, and every 3 months after that. If your eGFR is below 30, check weekly at first.

Are there new medications that help manage high potassium without stopping my heart drugs?

Yes. Two FDA-approved potassium binders-patiromer (Veltassa) and sodium zirconium cyclosilicate (Lokelma)-pull excess potassium from your gut. They allow you to keep taking ACE inhibitors and potassium-sparing diuretics safely. Studies show 89% of patients who couldn’t tolerate the combo before can stay on it with these drugs. They’re not first-line, but they’re a game-changer for high-risk patients.

Is hyperkalemia reversible?

Yes, absolutely. Mild to moderate hyperkalemia often reverses with dietary changes, diuretic adjustments, or potassium binders. Severe cases (above 6.0 mmol/L) need urgent treatment with IV calcium, insulin, and albuterol to stabilize the heart, followed by long-term management. The key is catching it early-before it causes heart damage.

Victoria Short

November 17, 2025 AT 22:50This is why I hate when doctors just throw meds at you without explaining the risks. I was on this combo for three months and never got a single blood test. I felt fine until I collapsed. Turns out my potassium was 6.2. Scary stuff.

Eric Gregorich

November 19, 2025 AT 15:24Let’s be real-this isn’t just about potassium. It’s about the entire medical-industrial complex pushing combo therapies because they’re profitable, not because they’re optimal. We’re told to trust the science, but the science is funded by pharma giants who profit from both the drugs AND the binders that fix the problems they created. It’s a beautiful, sinister loop. We’re not patients-we’re revenue streams with hearts that beat until they don’t anymore. And don’t get me started on how we’re guilt-tripped into eating ‘healthy’ foods that are just potassium bombs in disguise. Bananas? They’re nature’s little time bomb wrapped in yellow skin.

Koltin Hammer

November 20, 2025 AT 02:06Man, I’ve seen this play out in my clinic. Patients come in looking fine-no symptoms, no complaints. Then their labs come back and their potassium’s through the roof. The worst part? They’re on the meds because they’re told it’s ‘life-saving.’ And it is-but only if you’re being watched. I tell my patients: ‘If your doctor doesn’t schedule your potassium check before you leave the office, ask for it. Don’t wait for the system to catch up.’ And honestly? The new binders are a godsend. I had a guy on spironolactone and lisinopril for years, potassium always creeping up. Put him on Lokelma, and suddenly he’s stable. He cried when I told him he didn’t have to quit his meds. That’s the win we need more of.

Phil Best

November 21, 2025 AT 13:32So let me get this straight-you’re telling me we’ve got drugs that can save your heart… but only if you’re willing to pay $1,200 a month for a fancy stool pill? And if you can’t afford it? Tough luck, buddy. You get to choose between dying slowly from heart failure or dying quickly from cardiac arrest. Brilliant. Just brilliant. Next they’ll sell us oxygen subscriptions. ‘Pay $300/month or your lungs get a little lazy.’

Parv Trivedi

November 22, 2025 AT 04:01This is very important information. Many people in my country do not know about this risk. I have seen patients stop their heart medicines because they were scared of high potassium. But they do not know that there are safe ways to manage it. Doctors should explain better. And patients should not be afraid to ask questions. Thank you for writing this clearly.

Willie Randle

November 23, 2025 AT 18:40Minor correction: The REIN study cited was published in 2002, not 1998. Also, the 18% figure for hyperkalemia with combo therapy comes from a 2005 JAMA paper by Böhm et al., not the 1998 study. Accuracy matters-especially when lives are on the line. That said, this is one of the clearest, most actionable summaries I’ve seen on this topic. Well done.

Connor Moizer

November 24, 2025 AT 15:25Stop being passive. If your doctor hasn’t checked your potassium in 3 months, fire them. You’re not a lab rat-you’re a human being with a right to know what’s in your blood. And if they tell you ‘it’s fine’ without showing you the numbers? Walk out. Demand your labs. Print them. Bring them back. If they’re too busy to explain? Find someone who isn’t. Your heart doesn’t care how busy they are.

kanishetti anusha

November 25, 2025 AT 05:20I’ve been on this combo for 2 years. My potassium was 5.8 last month. I didn’t know what to do. Then I started tracking my food with an app-cut out tomatoes, potatoes, and salt substitutes. My potassium dropped to 4.9 in 3 weeks. I didn’t even need a binder. Small changes matter. Don’t feel helpless. You have more control than you think.

roy bradfield

November 25, 2025 AT 05:25They don’t want you to know this, but the potassium binders are just a distraction. The real agenda? To keep you dependent on expensive drugs so you never leave the system. They know if you ever get off the ACE inhibitor, you might live longer. So they give you a $1,000 pill to keep you hooked. And the SGLT2 inhibitors? They’re just the next big thing they’ll market as ‘the solution’ while quietly hiding the fact that lifestyle changes-like reducing processed food-would fix 80% of this. But that doesn’t make money, does it? Wake up.

Patrick Merk

November 26, 2025 AT 16:50Love this breakdown. I’m a pharmacist in Dublin and I’ve seen this exact scenario a dozen times. The best part? When patients realize they can keep their heart meds and just tweak their diet or add a binder. It’s not about fear-it’s about empowerment. I always tell folks: ‘Your meds aren’t the enemy. Ignorance is.’ Knowledge is the real potassium binder.

Liam Dunne

November 27, 2025 AT 10:56Just want to add-don’t forget about magnesium. Low magnesium makes hyperkalemia worse and is super common in people on diuretics. A simple blood test for Mg++ can save you a lot of trouble. I’ve had patients with recurring high potassium who were perfectly fine once we fixed their magnesium. It’s not flashy, but it’s critical.

Vera Wayne

November 28, 2025 AT 07:05Thank you for this. Seriously. I’ve been waiting for someone to lay this out like this. I’ve got heart failure, diabetes, and an eGFR of 42. I’m on lisinopril and spironolactone. I’ve been checking my potassium every 3 weeks since I read this. I cut out the bananas, the oranges, and the salt substitute. I started using the potassium tracker app. My last level was 4.7. I’m alive. I’m stable. And I didn’t have to give up my meds. You just gave me back my life.